IN CONVERSATION: Lauren Faigeles and James Siena: Moderated and Text by Nicole Kaack

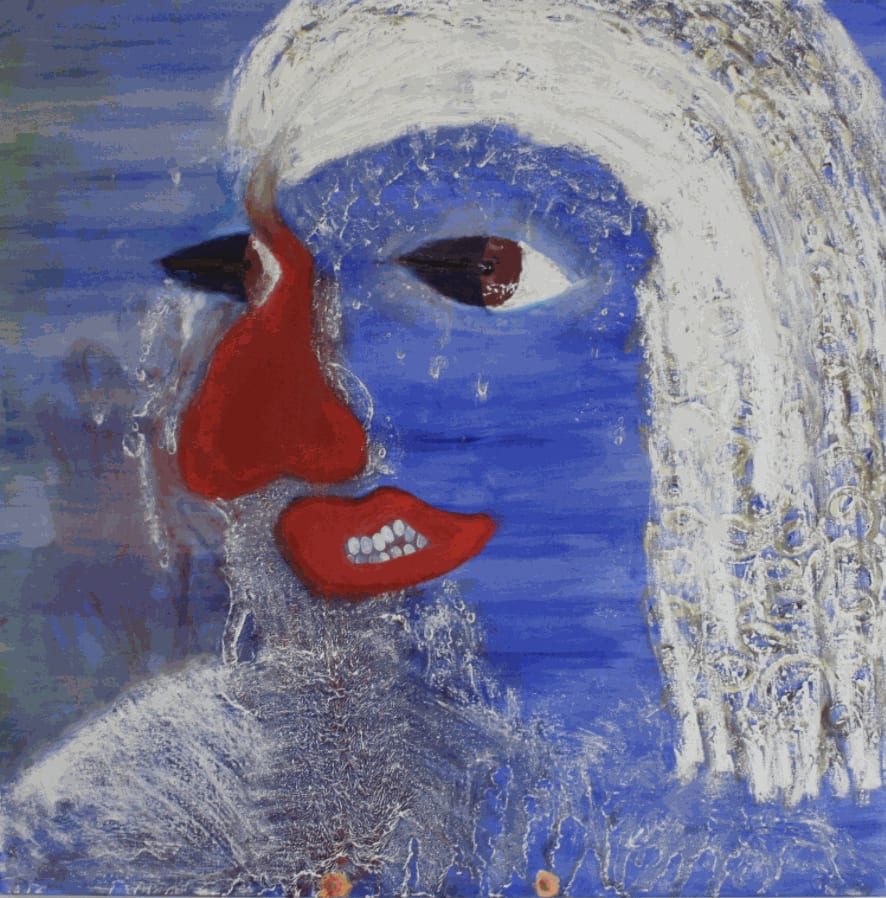

A game of Twister is written in the trailing marks of red, green, yellow, and blue spots, smeared and spread by the inexorable slide of splayed fingers. In a tooth and nail insistence on the artist's hand — spotty, white teeth literally applied with the fleshy pad of a single digit — Lauren Faigeles writes irreverent reinventions of a painterly “gestural." Playfully rebuffing the figural techniques of a medium that has, for so long, belonged to a masculine gaze, Faigeles depicts the same full-bodied form in bubbling daubs of pure pigment. Drawing from and proposing alternate embodiments to a canon including Yves Klein, Julian Schnabel, and David Salle, Faigeles both refers to her heroes and exorcises them, capturing the splashing marks of human forms in goopy blobs and completing a canvas with the bristly mustache of a collaged paintbrush.

James Siena: When I look at that Hitler painting, I always remember what Mel Brooks said when he got his Tony award for The Producers. He got up to the podium to accept the award —usually people thank others— and he said, “First of all, I want to thank Hitler for being such a funny guy.” He got into a lot of trouble for saying that.

Lauren Faigeles: I love that speech. Mel Brooks is really funny. I’ve been thinking about “Springtime for Hitler” the last few days. I do feel like spirituality does play a role in my work — I actually grew up in a more religious household and have been praying every day now, since my father passed away. In the Jewish religion, we say a Mourner’s Kaddish, so I’ve been doing that every day. It’s been bringing me back to a more spiritual, religious self from when I was younger. Because my work is funny or overly sexual, people never see the spirituality in it. But I invest my work with many of my beliefs and a lot of trust goes into my process of making, especially with these pieces. Like, in that painting, I just really liked that green color. So I just put a bunch of it down, and trusted myself to figure out what it was. I found this man underneath. It actually says, “I love you.” No one ever picks it up because it’s so easy. There is a love in my work, and I think the reason why I like to deal with tougher subject matter is because we don’t always think that these oppositional ideas are conjoined, that with love there’s hate. Everything contradicts itself.

Nicole Kaack: Perhaps that there is a spirituality in it but not in the sense of the cult of the artist, which is potentially more about that tradition of painting, of masculinity. You’re responding to that, representing the female body as you do, bringing a representation and realism that is also abstract.

James Siena: The materiality of that painting is very human. Very animal, mucus-y.

Lauren Faigeles: James, actually, gave me good advice on that one. It was just the yellow and the figure, the legs. He said, “Why are you using the white of the canvas? Why don’t you paint in white?” I was like, “Great idea, James.” I did.

James Siena: I don’t remember that.

Nicole Kaack: Part of the show was this series of drawings that you were doing in the gallery, being surrounded by your work, but also engaging with visitors. Is that something that you’ve done in the past as a practice? Or was this a newer thing?

Lauren Faigeles: Unfortunately I wasn’t able to be here much of the month, because I was sitting shiva in California with my family. But I do like the idea of being in a room with someone while they read my books, look at things. I like for people to be able to see my work in comfortable, safe environments like my studio. The one weekend I was here, we were making coffee for people. I like people to get comfortable, to be able to draw and touch, to talk and sit with things. And come back. I definitely want to keep working on my books, and maybe zines. It’s something I haven’t figured out. But hopefully it’s something I can work on in the future.

Nicole Kaack: Does anyone have questions for Lauren or James?

[Audience member]: I think some people might look at your work and say there’s a lot of intuition in it, but I really like the word ‘trust.’ Maybe you could talk a little bit more about that.

Lauren Faigeles: That’s an interesting point. I want to think about it. All I can think about now is that, usually, I would be making a lot of jokes in this situation. But at the moment, all I can think about is my father. He was a really lovely man, and very supportive. He’d always say, follow your passions. He loved me being an artist. In terms of trust— In the work I make, all this subject matter is rolling around my subconscious, all these things that I want to deal with. I could literally just think, “Okay, I’m going to make a piece about hearts.” Or “I’m just going to put down a shade of green, and that’s going to be it.” I just believe that all of these ideas will naturally come up. Sometimes artists end up being too in their head, where they feel that they have to figure everything out beforehand. I like it as a more intuitive thing where I can figure it out as it goes. These paintings are all made in the same time frame, but I usually have pieces that I work on for years. Like that piece [pointing] only took a day. I always think I will finish every painting that I start in a way that I would be able to put in a show. I don’t know the timeframe in most cases, but if I put something down, I know I’ll figure it out eventually.

James Siena: I would offer another word, besides intuition and trust. I would also think of the word ‘instinct.’ She has good instincts. You fill your head with things you’re curious about. So you don’t have to think that hard, consciously, and plan. You react to a green shape. You make a move, and then the world finds its way into your work.